The eerie grandeur found downtown in the cities of Old Europe is due to the fact that every centimeter is steeped in history. In the Netherlands, it’s a given that a place of contemporary popular appeal—say, a dance club or a boutique hotel—may inhabit a spot with hard-core historical gravitas.

What makes The Village Coffee’s second location in Utrecht, the Netherlands’ fourth-largest city, particularly haunting is that the previous site was in use right up until mid-2014: it was a prison. And although it began functioning as such only in 1856—somewhat recent by European standards—Wolvenplein (“wolves square”), as the property is called today, occupies canal-cradled land in use since 1580, when it was a military bulwark. In other words, discipline and control were the MO on this spot for centuries.

So you may appreciate both the irony and the aptness of the aesthetic to the owners now established on Wolvenplein.

“We like punk rock and metal,” sums up co-owner Angelo Van de Weerd.

Sitting in The Village’s spacious Wolvenplein courtyard among customers enjoying the sun and some hens roaming freely, the inked-up Van de Weerd and partner Lennaert Meijboom are wearing rock Ts (Motörhead and Black Sabbath, respectively) and slim black jeans. Both are warm and smiley, more likely to cuddle a chicken than to bite its head off.

Reflecting on their first location, which opened on nearby Voorstraat in 2011, they acknowledge the role The Village Coffee & Music—so named for its double-life as an espresso bar and small gig venue—took on.

Says Van de Weerd: “There wasn’t really a place for the—I hate the word—‘alternative’ scene to hang out. But when The Village [came to] the Voorstraat, people met each other [there], and it was really cool. That’s how we introduced [that crowd] to good coffee. Via [Wolvenplein] we want to introduce them to good food and good beers, and how you roast coffee.”

In fact, more than anything else, it was room to start roasting that sent them up the river.

“It’s kinda difficult to find a place in Utrecht, in the center, where you can have a [roasting] area and a part that’s a restaurant,” explains Meijboom. “We were searching for more than two years to find a good location for the roastery because we didn’t want to start off in some industrial area.”

In June 2014, Wolvenplein’s last prisoners were transferred to other jails. By June 2015, as nearby spaces were being rented to entrepreneurs and artists, Meijboom and Van de Weerd had set up shop.

Despite the barred windows (a feature left over from the building’s previous life), the cafe feels breezy. A front entrance works with one to the courtyard to provide favorable ventilation. Mid-century modern furniture, properly framed posters, and vases of fresh flowers counter any lingering correctional-facility vibes. The three-group La Marzocco Linea Classic is pure eye candy: customized by Dutch design studio Zink, the Z3 model’s glass panels reveal a powder-coated canary-yellow boiler.

The kitchen, which produces day fare all week and evening victuals on Fridays, uses bread baked in-house and ingredients sourced by blue-ribbon restaurant wholesaler Lindenhoff. Beers on tap include Jailbait Pale Ale, brewed for The Village by fellow Utrechters De Kromme Haring, and vino comes from Margaret Wines, a local supplier favoring small, traditional vineyards.

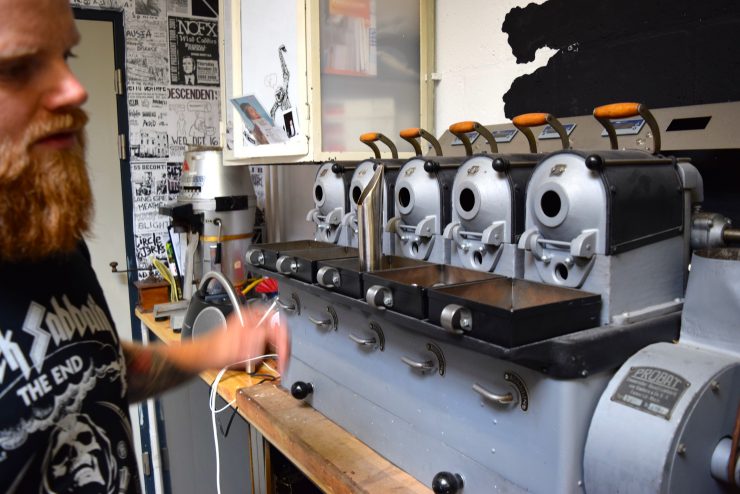

A separate room, described by Meijboom as the former prison’s management center, is where the magic happens. Van de Weerd roasts on a Probat UG15 from 1955, with sample roasts coming through a smaller, self-restored “old Probat, also 1950-something,” he says. Barstools invite visitors to sit and watch, while they in turn are watched by the wizard on the facing wall’s mural.

The Village serves its own roasts in all three of its locations—an espresso bar opened on the Utrecht Science Park university campus this past December—as well as distributing to businesses across town. At Wolvenplein, a pair of Anfim Super Caimano grinders stand at the ready, whether for the Outsider, a blend of 75 percent Colombian and 25 percent Ethiopian coffees; the Renegade, a blend of 50 percent Brazilian and 25 percent each Colombian and Ethiopian; or one of the weekly filter coffees or single-origin espressos.

Meijboom and Van de Weerd, now in their 30s, grew up in Wijk bij Duurstede, a town with the Netherlands’ only drive-through windmill. They connected over music and at festivals, which they attended at first just as fans; eventually, they began working at them, selling coffee and sharpening their skills. By 2008 they found themselves as spectators at the World Barista Championship in Copenhagen. “We started being really serious about coffee,” Meijboom recalls. A year later, Van de Weerd came in fourth at the Dutch Barista Championship.

Planning to hit nine of them this summer alone, music festivals remain important to The Village duo. Nowadays, though, the friends also attend to pursue their living, building up an espresso bar at nearly every location. When not on tour, they often can be found hosting movie nights and air-hockey matches at Wolvenplein or programming punk shows at music venue EKKO.

Angelo Van de Weerd and Lennaert Meijboom

Yet for all that activity, The Village has no plans to become an empire.

“We’re not really [doing it] to expand a lot. We just want to do stuff that feels good, do cool things,” says Van de Weerd. “Sometimes something pops up, [like] people ask you: ‘Oh yeah, do you want to open a bar in a prison?’ And we’re like: ‘All right, let’s do it!’ But we don’t want 20 Villages.”

Besides, Meijboom and Van de Weerd are now doing everything they ever wanted as coffee professionals. What’s more, they get to operate within a property where thick bars still line the central hall’s cell-stacked atrium and the solitary confinement spaces, not exactly scrubbed clean, were obviously very much occupied. It doesn’t get much more heavy metal than that.

Karina Hof is a Sprudge staff writer based in Amsterdam. Read more Karina Hof on Sprudge.

The post Heavy Metal Coffee In An Old Dutch Prison At The Village Wolvenplein appeared first on Sprudge.

seen 1st on http://sprudge.com

No comments:

Post a Comment